“ A Dispositif is (…) a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions – in short, the said as much as the unsaid. Such are the elements of the dispositif. The dispositif itself is the system of relations that can be established between these elements. Secondly, what I am trying to identify in this dispositif is precisely the nature of the connection that can exist between these heterogeneous elements." Michel Foucault 1977.

))) A brief resume of the original paper (((

What is

Monumentality?.

Most common definitions of monumentality are

fuzzy and imprecise, as if there was an intuitively comprehensible significance

for what a monument actually is: a

spatial landmark inherited from the past, which operates – voluntarily or not-

as the remembrance of some remarkable person, idea or event worthy of imaginary

perpetuation. From this perspective, the monument obtains its essence from its

historical value: its intellectual content is fully produced by the

accumulation and representation of the passage of time upon it. By giving

visibility to history in our built environment, Monuments are fundamental

tokens for the production and consolidation of social identities, inasmuch as

any community´s uniqueness arises from its particular entanglement of memories

and oblivions. Therefore, far from being merely a piece of an anthropological

archive that gives neutral testimony of cultural expressions from the distant

past, monumentality is experienced as the materialization and embodiment of

eternity, or the radical continuity between past, present and future inscribed

in objects. As we see in these pictures (taken from Google images) of the most

popular monuments in York,

contemporary

society considers that any artifact from ancient times is

likely to be considered a monument. But many of these

buildings were not raised at the time with the intention of functioning as monuments. They have been monumentalized

afterwards through complex aesthetic, social and epistemic processes.

So I will list some of the most significant features of the classical

conception of monumentality, in order to clarify and define what gives the monument its

specificity in the built

environment.

The monument is a memorial.

First and foremost, strictly speaking, classical

Monuments were consciously conceived as Memorials. Their key function is commemoration: the collective celebration

of common memories likely to become the core of a society’s consistency. From a

Hegelian standpoint , the monument is thus the fundamental political

device, for it’s indispensable for a Nation to exist as such. the monument is

the totemic place or object that embodies the collective ideology by means of

symbols and rituals that exhort the individuals to affirm their membership and loyalty

to a Nation or a creed, fostering a sense of belonging to a group. This

collective identity coalesces around traumatic or meaningful events that get

monumentalized and thus perpetuated as sacred material presence.

The monument is a landmark.

They were not built for the visitors, but quite

the contrary: they were private to the community, as an expression of the

ownership of the land, that is exhibited dialectically as opposed to the

community´s outside: the obelisks of the Roman Empire were not only a

celebration for the emperor, but also

against the barbarians. We could

trace the territorial limits of the empire by locating the monuments they were

able to erect. According to Ernesto Laclau’s analysis of the

floating signifier, any community –and any Nation- must be constructed in

dialogical relation to its outside by means of semiotic expression. Commonality

is constructed oppositionally, by the production of boundaries, by means of

totemic symbols that delimit and articulate the extension of the community,

both in the domains of physical spatiality and ideological subjectivity.

Henceforth, the monument’s essential commitment is to locate the community’s hegemonic

semiosphere into space, namely, to give form and signify the specificity of the

Local – as opposed to the universal. In a sense, then, monumentality

establishes the basis for the deployment of the privacy shared by the members

of a community –a privacy that constitutes its fundamental feature. Historically,

after a war

the enemy’s monuments

became trophies that demonstrated

a successful conquest. Monuments are

thus signifiers of power, instruments of Law. Their iconicity is parallel to

their originality and singularity: no monument can be reproduced or copied, since

their identity is correlative to its spatiotemporal location.

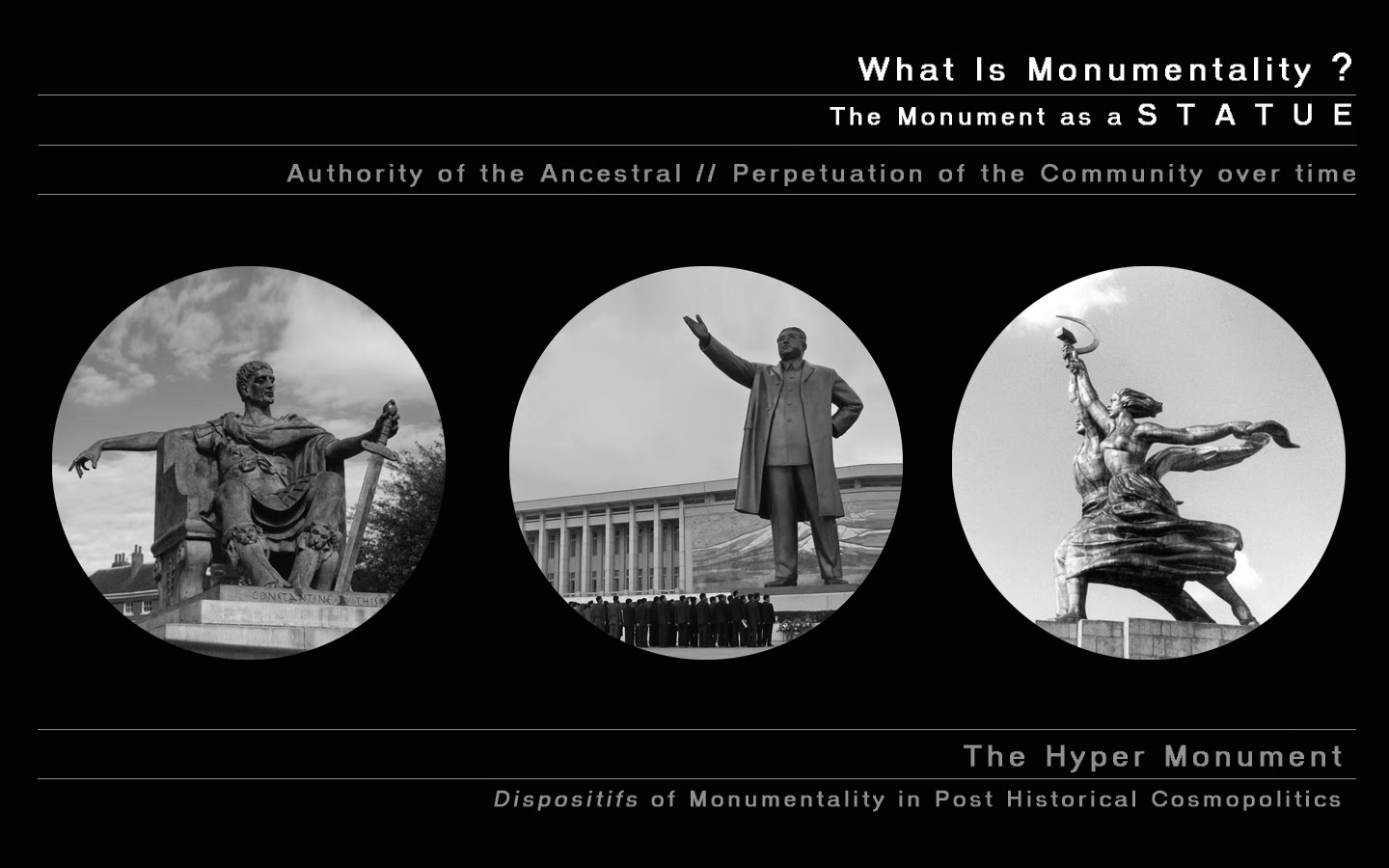

The monument is a Statue.

In his book Le second livre des foundations french philosopher Michel Serres traced

the original political meaning of statues: The imperturbability of the statue of a dead

emperor –as opposed to the finitude of its corpse-, allowed mankind to conceive

eternity, or identities as extemporaneous, immortal substances. Embodied in

stone, the soul survives the body and sets the possibility for thanatocracy

(the governance of the dead), as authority becomes trascendent, above and

beyond present time. If the Statue was the effigy of a remarkably powerful

person, the Monument is the effigy of a significant event. The materiality of

the monument is hence inseparable from its narrative or mythological content:

the memorial signifies, celebrates and perpetuates ancestral institutions of

governance. As the

primary representation of a society’s collective imaginary, the monument –may

it be architectonic or not- operates as the immanent political foundation of a

communal “spirit” that modulates the

ways in which its participants deal with the symbolic significance of objects:

at first, monuments signify the authority of the ancestral, and

delimit the community from the menace of disappearing over time.

The Monument is a Temple.

Every memorial necessitates some sort of ritual

gathering to guarantee its permanence in the collective symbolic regime. One of

the fundamental performances of monuments is their role as places of active

congregation and celebration: the community most often organizes regular

ceremonies that commemorate the persons or events that the monument recalls. Beyond

pure contemplation, the monument mediates between the individual subjectivity

and collective systems of beliefs by means of ruled celebrations and ritual

practices where its narrative content is staged as participatory practices- not

necessarily religious.

19th

Century crisis in Monumentality.

But in the mid nineteenth century this canonical

consideration of monumentality went into crisis. A series of cultural

transformations coalesced as the industrial revolution, the modern idea of

universalism and the expansion and acceleration of international intercourses

of all kind set the basis for a new articulation of the local and the global,

the individual and the collective, ancestrality and authority, past, present and future. Moreover, the rise

of mass tourism radically altered the role of monumentality in the urban

imaginary

Institutional architecture goes through a period characterized by revivalim

and pastiche, through eclectic recreations of former monumental languages, in

line with one of the great contradictions of post-romanticism: on the one hand

an optimistic confidence in universal, never-ending progress ( the utopia of a

peaceful and prosperous cosmopolitanism), and on the other the nostalgia for a

past that retains its aesthetic appeal, but devoid of the political and social

connotations it once had. In this context of transition from the old regime to

the industrial era, the emerging bourgeoisie is seeking hard to find a specific

architectural language likely to illustrate the most suitable Monumentality for

the new zeitgeist.

Universal Exhibitions.

Significantly, during the second half of the nineteenth century the so-called

"Universal Exhibitions" were born, as international meetings in which

different nations presented strongly iconic theme pavilions aiming to

illustrate the technical wonders offered by the engineering and industrial

progress.

The construction of the Eiffel Tower for the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889 was the

zenith of the new monumentality. Facing the previous historicist architecture that

intended to recreate the forms of the past, the tower expressed a new

collective attitude towards history. Monumentality was finally released from

the ancestral and apparently emptied of any political content. The tower is a

monument that does not commemorates any significant event or national trait,

but seeks to illustrate a utopian future whose harmony is guaranteed by

technological progress and universal cosmopolitanism.

20th Century.

The conversion of technology into urban spectacle, internationalism and the

break with the past is perpetuated throughout the twentieth century in most

buildings that aspired to acquire a monumental dimension, such as the Sydney

Opera House, the Empire

State Building

or the Guggenheim Bilbao. Futurism supersedes historicism.

Freud.

But the new configuration of monumentality in the twentieth century not

only affected the newly created monuments, but also the role that older monuments

play in our collective imagination. The political, symbolic and aesthetic link

between past, present and future entered into a crisis that some authors

referred to as "the end of history" with its many derivatives: the

End of Art , the end of humanism, the end nation states, and even the end of

reality. This cultural atmosphere of questioning the role of history in the

present days, took Freud to analyze the nature of monumentality as part of his

general theory of culture. In his 1917 essay "Mourning and mellancholly" Freud states that any monument expresses

a collective sense of loss, a traumatic event that ends in an absence or

longing for what was lost, and is perpetuated in the collective identity by

adquiring a legislator role . With this starting point, he developed his theory

of the role of commemoration as the founding process for the individual to

become a member of a community, or congregation. According to Freud, by building a monument,

societies create an externalized location that becomes involved in the shared

mourning process.This

correlation between monument and authority is plausible in the definition of

the superego given in "The Ego and the Id": "Superego is the

memorial of the former weakness and dependence of the ego, and the ego mature

Remains subject to its domination." (The monument is therefore the

symbolic embodiment of a form of authority).

If, as Freud states, monumentality implies the

mourning for some traumatic loss, in the case of postmodern tourism the loss is

history as an ongoing process. Ancient monuments become memorials for universal

Historicity in general. German philosopher Boris Groys reflected upon this contemporary

cosmopolitical and post-historical milieu in his analysis about the tourist

gaze. By recovering the ideas of Alexandre Kojeve (the philosopher who

presented the concept of “the end of history” for the first time), Groys states

that the way the tourist looks at historical objects monumentalizes them by

recognizing the radical discontinuity between the past that they embody, and

the present. Henceforth, the positive universalism of Posmodernity and the

distancing from mythical beliefs of the past, necessarily elicit a gap or

imparity between history and post-history, that can be experienced by visiting

the monument. Ancestrality is no longer experienced as authority, but as otherness.

Hyper- monumentality.

As we said, the popularization of mass tourism fosters universalism and

globalism. Tourists enjoy the Notre Dame cathedral without necessarily being

catholic, for cathedrals are monuments not only of Christianity, but rather of

the overall history of mankind. Monuments are no longer honored and used

exclusively by the collective that provided them with their former narrative

content, and pass to belong to humanity as a whole, through the appearance of a

new cosmopolitanism that urges citizens to enjoy the visit of foreign memorials

without identificating with the authority they represent. When the former symbolic content of

the memorial is considered illusory and sterile myth by the postmodern

beholder, monumentality is transformed

into what I´ll call hyper-monumentality

The tourist cult of historical artefacts

expresses his intimate feeling of distance from history, the

radical hiatus implicit in the post-modern sense of chronology as disrupted

from the teleological continuity of historical temporality. The monument

dies and becomes a fossil of itself, but its corpse gets mummified and revives

as a memorial of Universal history. It no longer pertains to a private

community, but to the whole of mankind as an undifferentiated unity.

Hyper-monumentality commemorates the otherness of history, and the obsolescence

of original monumentality.

In the hyper monument, history is devoid of its

former jurisdiction and its political foundation, and past events are frozen in

a chronological limbo, radically discontinuous with present developments. The “memorial” becomes a simulation,

illustrating the triumph of global, pan-humanist ideology over former local or

private cosmogonies. The Hyper-monument profanes the sacred myths and doctrines

that gave sense to the monument in the first place, and commemorates history as

a sterile, harmless set of aesthetical delights. Deprived of sovereignty, the

whole History becomes picturesque. Former

rituals and ceremonies are superseded by the universal rite of taking

photographs.And such a cultural passage has strong political

connotations, for it extracts people’s identity from their chronicled roots,

and re-locates it in the post-modern experience of time as hyper-present and

global synchronicity. History becomes hyper-story.

Besides, by getting hyper-monumentalized, historical

monuments become extremely important economical devices in many countries and

cities where the GDP is dependent on tourism income: they become commodities,

and as such they are submitted to all sort of marketing strategies that aim to

create a specific aura for them. The former symbolic value of the monument is

replaced by its economic value..

The hyper-monument is thus an extraordinary dispositif for the worldwide spread of

the cosmovision of globalization.

Dispositifs of

Monumentality.

The original monument was the flagship of a

Nation’s particular and hegemonic inter subjectivity, while its contemporary

significance has turned merely iconic, universalizing and post-historical. This

progression is equivalent to the passage from syncretism to monotheism: monuments

were formerly as diverse as the different cultures that produced them, but

after the globalization the new hegemonic usage of Memorials has turned, as

Deleuze and Guattari foresaw, from the narrative to the purely sensorial and sensational. The multitude celebrates itself through the universal

and undifferentiated experience of “visiting

monuments”. The images from the remote past have acquired the status of

phantasmagoria, or what Jacques Derrida

called "the paradoxical state of the spectre, which

is neither being nor non-being”. Hyper monumentality may so be seen as the

disguise by which post modern societies try to hide the powerful significances

inherent to the original monument, by a camouflage strategy that what could

only be dismantled by means of what Derrida called hauntology, an endeavour that should be minutely developed on

further monumental studies. The spectre of History is embedded in the

hyper-monument –which is a paradoxical mummification of history’s concluded

dynamism with its vigour weakened to (seemingly) death.

In this picture we see a resume of some of the

transitions derived from the passage from monumentality to hyper-monumentality:

The memorial of particular events becomes

memorial of universal history.

The landmark of the local becomes an Icon of

the global.

Ancestrality as authority becomes ancestrality

as otherness or myth.

The privacy of the community becomes the universality

of the whole mankind

The symbolic or narrative value is superseded

by economic value.

What was ruled by local laws is now subjected

to international legislation.

And as we´ll see, Simulation becomes

dissimulation.

Hyper reality.

On his investigations about cultural simulacra,

Jean Baudrillard defined the

opposite semiotic acts of simulating

and dissimulating. "To dissimulate,"

Baudrillard has written, "is to pretend not to have what one has. To

simulate is to feign to have what one doesn't have” . According to such

approach, Disneyland may be the paroxysm of

simulative artefacts, for its entire aura depends on fake castles, false magic,

illusional characters and all sorts of spatial fictions: it replaces its

inexistent history by means of pure hyper-symbols that are reminiscent of

certain daydreams shared by its potential audience. The hyper-monument may

reversely then be considered pure dissimulation, since the original political

potentiality has been hidden under the purely aesthetical surface, so that the

commemorative function can be replaced and normalized for the global denizen

that inhabits hyper-reality.

Finally, the difference between the classical

monument and the post historical hyper-monument is not clear cut. Monumentality

is a matter of experience: it doesn’t rely exclusively neither in the object

neither in the beholder. Ontologically, Monumentality appears as a particular

relationship between the Subject and the Object of his contemplation: its

therefore a relational event, that depends of meaning, subjected to the

fluidity of the correlation between the signifier and the signified. Its an

affection. Every artefact is likely to acquire new significances over time. A

general theory of Monumentaly should be a theory of objectified memory. Or

entombed memory.

We see in these pictures the Brandemburg Gate

under different hegemonic regime:

In the 19th Century.

During the Third Reich.

During the Cold War.

During the fall of the Berlin Wall.

During a U2 Concert.

During the Gay Parade.

...and any day, today.

The importance of this debate has to do with power

and law: when a site is deemed to be Monumental, it renders it exceptional in

all senses. And worth of perpetuation, immune to the rapacious, cannibalistic

and unstoppable urban mutations. Who decides what is really a monument? Where are

our collective shared memories really incarnated? Which are the temples of our

identities?

fantastic!

ResponderEliminar